Subtotal $0.00

Inside the Ocean

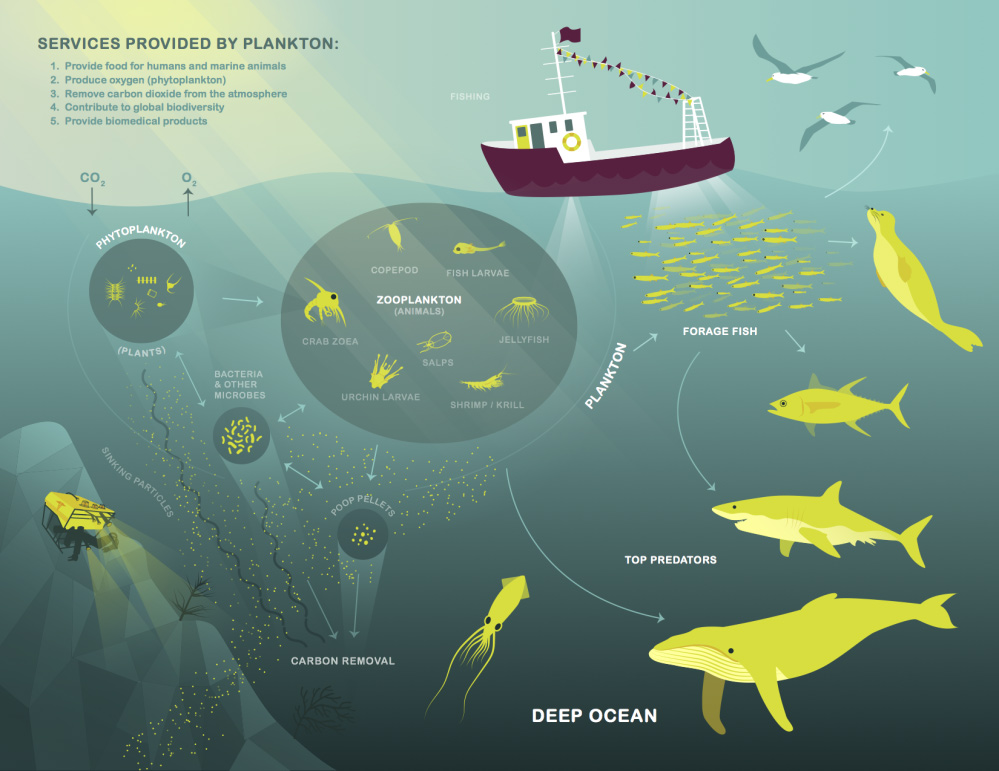

Plankton are a critically important food source. Plankton also play an important role in the global carbon cycle. This cycle captures the Sun’s energy and the atmosphere’s CO2 at the surface of the ocean and releases it to other organisms and other areas of the ocean. Understanding where and when plankton occur at different depths in the ocean allows scientists to get a global understanding of the function and health of the ocean from small to global scales.

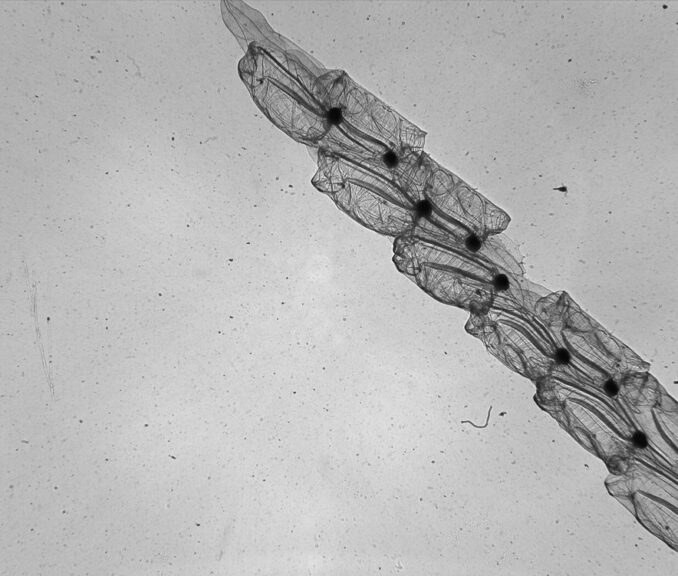

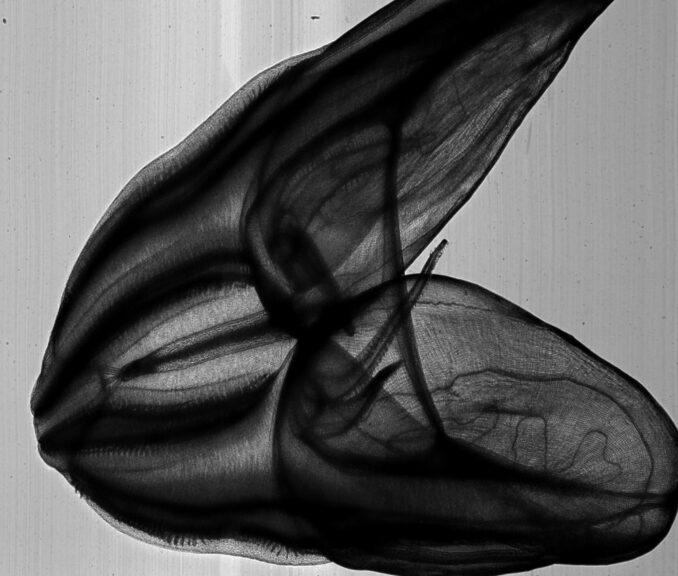

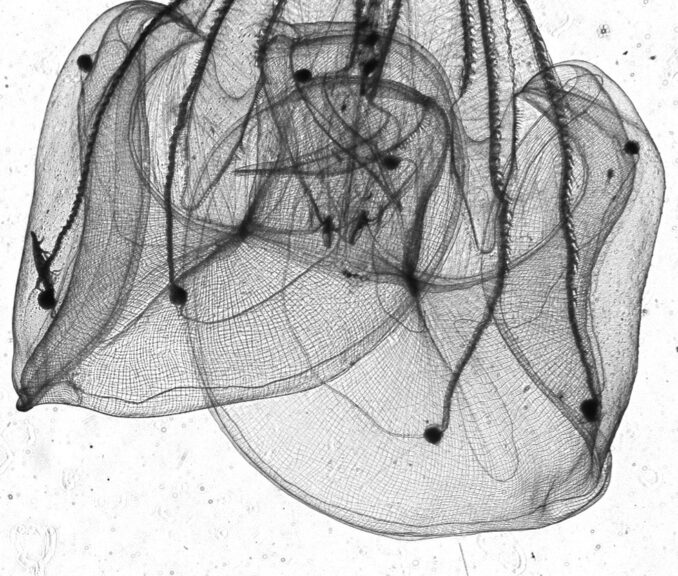

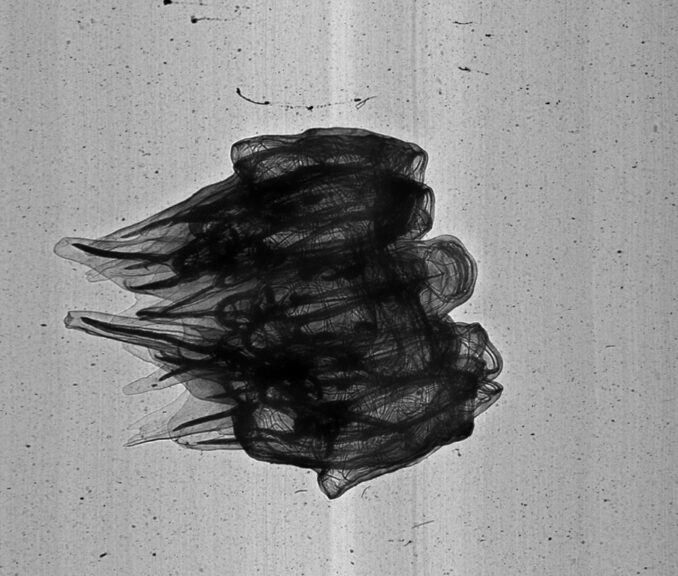

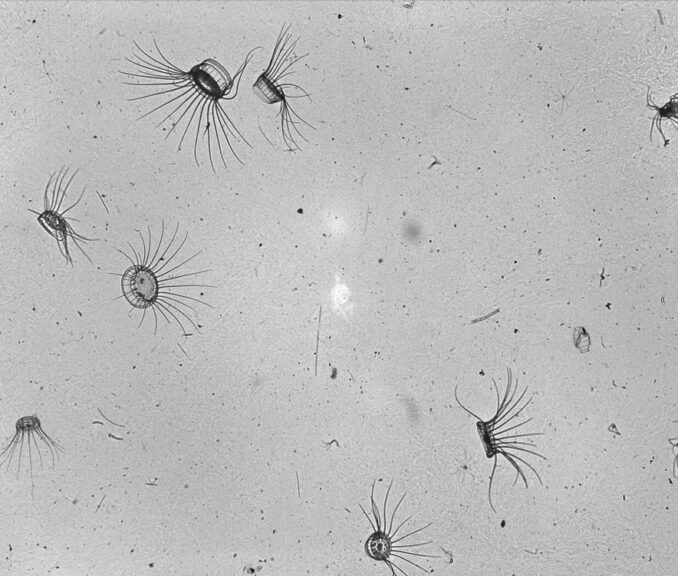

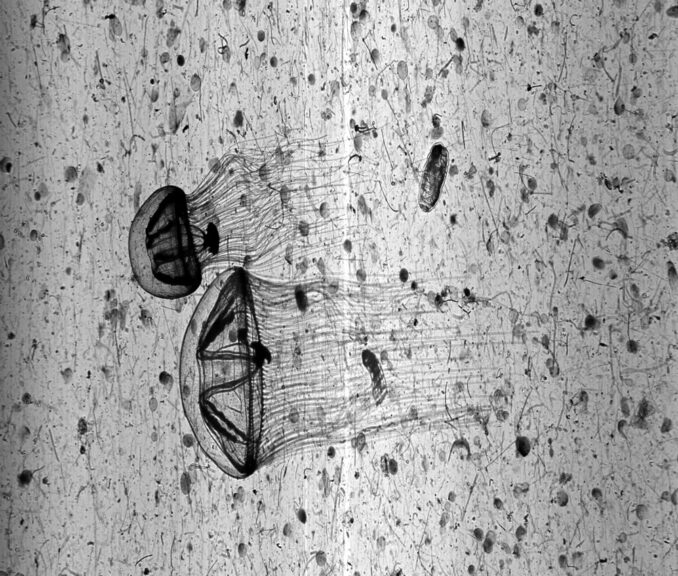

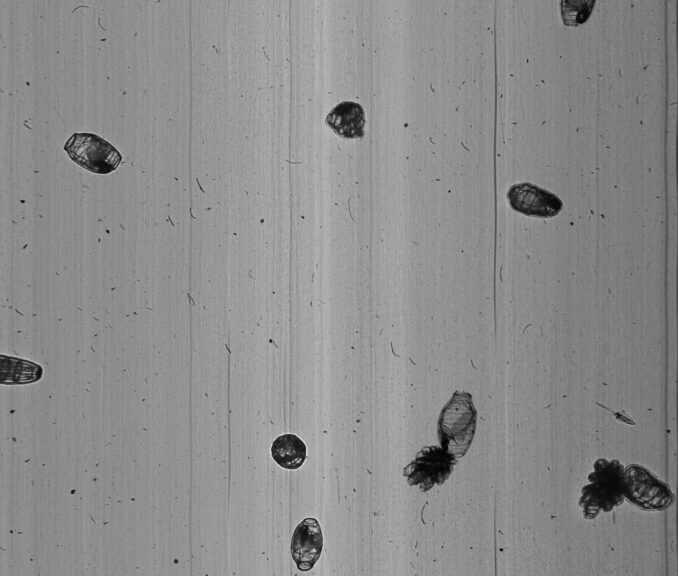

Traditional plankton sampling destroys the very thing it tries to measure. ISIIS-DPI changes that. The ISIIS-DPI Plankton Imager is an in situ imaging system designed to observe plankton communities at their natural scale and distribution. It captures high-quality images of plankton, gelatinous organisms, and marine particles in-situ, while sampling large volumes of water at fine spatial and temporal resolution. ISIIS-DPI systems can be configured with line-scan cameras for constant-speed towed surveys, typically around 5 knots. An Area-scan camera configuration provides for more flexible operations such as variable tow speeds, vertical profiling, and stationary deployments. This versatility makes ISIIS-DPI a field-proven platform for studying plankton ecology, trophic interactions, and biological–physical coupling beyond the limits of traditional sampling methods.

High Volume Sampling

High volume sampling at high acquisition rates

High Resolution Clear and detailed image quality

High Water Speed

Capability to operate in fast-moving water 5 knots+

Publications Extensive research and studies 80+ Publications

Particles Imaging Plankton, oil droplet & gas bubbles images

Oceanography Use in oceanographic research

Limnology Limnology, Mesocosm & freshwater studies

Different research questions require different optical configurations. ISIIS-DPI is therefore designed as a family of imaging systems, allowing researchers to select the configuration that best matches their scientific objectives.

| ISIIS-DPI | Size | Volume | Speed | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P125 | >1mm | 4 L | 6 kt | LTER transects, Ecosystem studies |

| P100 | >500µm | 0.74 L | 3.25 kt | Community-scale surveys |

| P75 | >300µm | 0.27 L | 3.25 kt | Copepods, larvae, gelatinous organisms |

| T424 | Phyto chains | 1 ml | Slow | Diatom chain identification |

| Benchtop | = P75 | N/A | N/A | Lab imaging, ML training |

ISIIS, short for In-Situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System, was originally developed in 2005 to image large volumes of water and study ichthyoplankton patchiness in the Gulf Stream off the coast of Florida.

As the system evolved, its defining strength became clear: the ability to image a large depth of field while capturing far more than just plankton. To reflect this broader capability, DPI was added to the name, standing for Deep-focus Particle Imager. Today, ISIIS-DPI is used to image a wide range of particles and organisms across multiple scales.

The ISIIS-DPI Plankton Imager uses Basler machine-vision cameras, selected for their high resolution and global shutter.

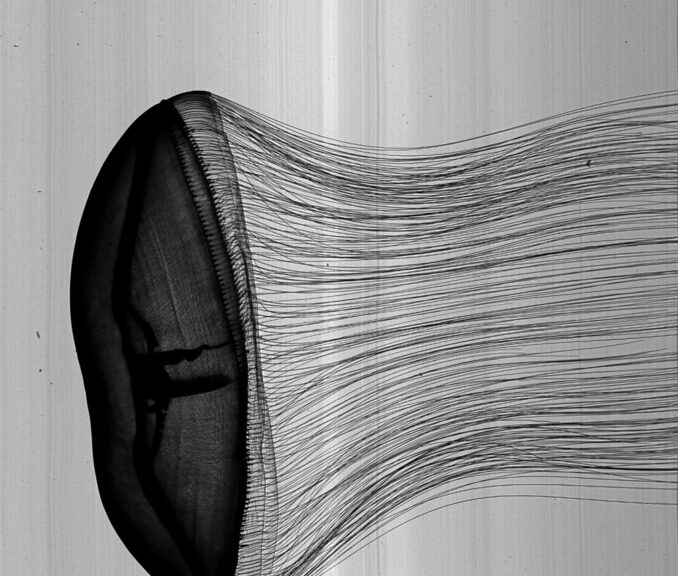

A line-scan camera builds a continuous image as particles pass through the field of view. This approach eliminates concerns about image overlap, sub-sampling, or counting the same organism multiple times.

Additional advantages of line-scan imaging include:

An area-scan camera, by contrast, captures discrete frames and may be more flexible in situations where flow speed varies or where imaging at rest is required.

Shadowgraphy does not require very high illumination, allowing operation near the minimum exposure time supported by the camera sensor. As a result, motion blur is generally negligible.

The primary exception is the T424 camera, which may require strobing when used in high-speed towed applications.

Pixel resolution depends on two factors:

For example, a sensor with 2048 × 2440 pixels imaging a 12 cm-high field of view results in: 120,000 µm ÷ 2048 ≈ 58.6 µm per pixel

In practice, an object requires 10–15 pixels across its smallest dimension to be represented adequately. In this example, the system would reliably capture organisms approximately 700 µm to 1 mm in size or larger.

Pixel resolution alone is highly theoretical and does not fully describe imaging performance. This is why ISIIS-DPI systems are specified using size recommendations, which account for resolution degradation across the depth of field.

At the focal plane, pixel resolution correlates closely with measurements obtained using the 1951 USAF resolution test chart. As particles move away from this optimal plane, either toward the camera viewport or the light projector, they gradually lose sharpness.

Most users configure the imager so that resolution degrades by no more than a factor of 2–3 across the usable depth of field. For example:

This empirical approach is straightforward to document and to test using 1951 USAF resolution test targets, which allows users to report a true resolution over their full depth of field.

To cover a wide range of organism sizes, several strategies are commonly used:

The imaged volume is calculated as:

Field of View area × Depth of Field × Image rate

Larger ISIIS-DPI systems are capable of imaging up to 80 liters per second per camera, enabling high-throughput, statistically robust sampling.